By Stephen Claypole, as told to George Wyndham

It was in October 1972 that I first saw Shanghai through the window of a CAAC Ilyushin 62, rapidly descending towards the original civilian airport at Hongqiao. Through an afternoon haze I marveled at the scale of the Huangpu River and picked out some of the stylish, historical buildings on the Bund. There wasn’t a skyscraper to be seen all the way to the horizon.

It was my great good fortune, at the age of 29 to be one of the first visitors to China as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution wound down and the leadership in Beijing began to reach out to the West. President Nixon had been there six months earlier, and the small group of which I was part was the pathfinder for a visit by the former British Prime Minister, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, then serving as Foreign Secretary.

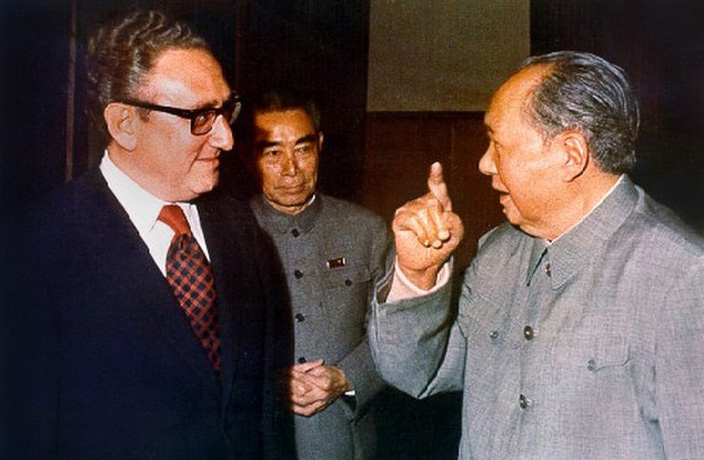

President Richard Nixon visited China in February 1972 to sign the Shanghai Communique.

Before his arrival we were offered the opportunity to see something of the country, at the suggestion of the diplomatic press corps in London and personally approved Premier Zhou Enlai. We were at the last gasp of what had been called ping pong diplomacy, when teams of international table tennis players, including the Americans, had been invited to the country for some sport - and usually a good thrashing by their hosts.

Just about every moment of my first day in China is fixed in my memory: the early morning crossing at the strict frontier post at Lowu on the border with Hong Kong, where our bags had been completely unpacked by Chinese customs officers; the ride up to Guangzhou on a splendid air-conditioned train (the only sign of modernity during a 12 day trip); and the official government welcome at Guangzhou railway terminal.

The journey had not been an easy one and the 20 members of my group were feeling nervous and apprehensive. On the train we had been battered with quotations from the little red book, Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, and revolutionary opera through the public address system. Every Chinese we encountered in public places averted his or her eyes, in spite of, or perhaps because of our long hair and 60s leftover fashion.

There on the platform at Guangzhou was the reassuring sight of two of the most urbane diplomats I have ever met, Mr Ma Yu-zhen and Mr Ch’i Ming-Tsun, desk officers from the Information Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Beijing, who accompanied us to Shanghai then on to the capital.

Unlike the ordinary Chinese we had seen, their Chairman Mao suits (blue boiler suits worn without exception by the entire population) were exquisitely tailored. They were bilingual and spoke with impeccable Oxford accents (acquired, we believed, while interrogating British officers during the Korean War). Mr Ma was to remain a friendly acquaintance for many years as he rose to the head of the Information Department and then became a distinguished Chinese Ambassador to London.

A Chairman Mao badge. Such badges were worn by nearly all Chinese people — including Premier Zhou Enlai — during the Cultural Revolution.

After take-off on the Ilyushin 62, we soon became aware that we were traveling on a most unusual but gracious airline – the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). Cups of green tea, large yellow apples and limp sticks of chewing gum were served by boiler-suited girls. For entertainment we got MAOZAK (sic) - recorded revolutionary opera on the public address system. When the temperature rose a little, the stewardess handed out traditional Chinese fans bearing illustrations of the class struggle.

One stewardess emerged with a fly swat and made for an overfed blow fly that had somehow evaded the Bureau of Public Security and boarded our flight. It was with some relief that we boarded a bus from the original civilian airport at Hongqiao and headed for the Peace Hotel, then an austere, dimly lit place smelling of tobacco, maotai and Shanghainese food - what we used to call the “whiff of stale kippers” in a British boarding house.

We saw very little of the Peace Hotel though. At this stage the Chinese authorities were at pains to demonstrate that the Cultural Revolution had not been the catastrophe that the West had believed it had been, and sage leaders like Zhou Enlai knew it had been.

We were constantly whisked by bus with motorcycle outriders to the “achievements” of the Cultural Revolution in hospitals, schools and shipyards. We drank countless cup of green tea in deep armchairs beside enormous spitoons, listened to endless briefings by the Vice-Chairmen of Revolutionary Committees and pored over seemingly impressive statistic with cadres of the Chinese Communist Party.

We constantly speculated on why we only ever got to meet Vice-Chairmen. Then the penny dropped. There could only be one Chairman in China, the revolutionary leader and veteran of the Long March, Mao Zedong.

On one bus ride an official picked up the microphone to inform us that the Cultural Revolution had eliminated all crime in the People’s Republic. As he spoke, we watched spellbound as the police chased an armed robber down Nanjing Road.

The highlight was a two-hour visit to a May 7th Cadre School, where lofty managers, officials and bureaucrats were sent for remolding in the image of the workers and peasants. There was a concert at which wayward cadres performed a dance, carrying zinc pails in glorification of pig farming.

The diplomatic press corps from London indulged its fantasies imagining a similar school in the UK with our employers Rupert Murdoch and Lord Rothermere ankle-deep in pig swill, learning to love the workers.

It was coverage of the concert that led to the first hiccup of the visit, if not quite a diplomatic incident. Murdoch’s man, John Akass of the Sun newspaper, wrote in his regular column that he had come to the conclusion that the entire Chinese nation had “lost its marbles.” For several days afterwards, officials asked for the “true” meaning of the English phrase “to lose your marbles.” We insisted it was a term of endearment.

Akass wasn’t far off the mark. During the darkest days of the Cultural Revolution - 1965 to 1968 - China had come close to losing its marbles. Now, in 1972, we could see through the propaganda to real achievements that happened in adversity and in spite of the constant ideological bombardments of revolutionary struggle. We all sensed that China was awakening and going places.

I spent a lot of time at No 9 People’s Hospital in Shanghai where acupuncture of all forms, but particularly anesthesia, were being demonstrated. We watched from the medical students’ gallery while a patient sporting more needles than a porcupine had a lung removed and immediately afterwards sat up and ate a bowl of rice.

On another visit to No. 6 People’s Hospital we saw world class techniques for rejoining severed limbs. The surgeons were leaders in the micro-surgery necessary for re-joining fingers. One imaginative surgeon had resolved the case of a worker who had lost both feet in an industrial accident by stitching the only salvageable foot – the left one – to the stump on the right leg.

Shanghai's Pudong region in 1972. Image via Shanghai World Financial Center Observatory.

On our final night in Shanghai the Revolutionary Committee hosted a banquet where there were many Maotai toasts to the Queen, Mao Zedong, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Fleet Street and Sino-Anglo Friendship. I awoke the next morning at 9am dehydrated and smelling of China’s number one spirit and fried rice. Hammering loudly at the door was Mr. Chi, “You have 15 minutes to join the bus or find your own way to Beijing!”

In the scramble to pack there was no time for a bath, and in getting dressed I ripped a pair of underpants. As I zipped up my case I threw them into a corner.

On the way to Hongqiao we stopped to meet the Revolutionary Committee at a shipyard in Pudong. We reached the airport at lunch-time and boarded another Ilyushin 62 for Beijing. As the doors were being shut a furtive character rushed up the steps. There was a hurried conversation then the stewardess picked-up a microphone and asked for me. “Gawd,” I thought. “Have I caused a diplomatic upset? Did I not give the right answer about the nation losing its marbles?”

The furtive character dashed down the aisle and handed me a package of brown paper tied with string. Inside were my ripped underpants, darned, washed and ironed!

Top image: Stephen Claypole at a Pudong shipyard with Ma Yu-zhen (left) who later became the Chinese ambassador in London.

0 User Comments