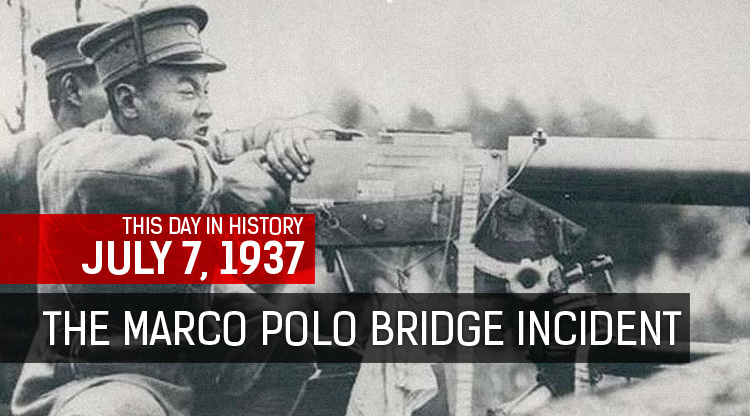

Adjacent to Shenzhen’s glass skyscrapers, a short bike ride from the Hong Kong border, live the founders of Feng Animation (风动画). Husband and wife team Chen Xifang and Zhang Minfang moved to the city in 1986 and met working in the same studio, during a period when outsourcing cartoon creation to China was big business.

Chen opens the door to greet me while Zhang makes a pot of coffee. The walls of their apartment are covered in murals that seem inspired by Mexico City. It’s cozy and relaxed, like a university cafe or even a youth hostel; a space that is in no way connected with China’s urban tribes of stiff-necked office workers.

Feng Animation began in 1996, producing award-winning short films. It was built off the back of a trend that started in the mid-80s, when a new creative class was settling in Shenzhen in order to make some of the West’s most popular cartoons.

Animation outsourcing started to take off in the southern metropolis not only because it was a Special Economic Zone, but because it was positioned beside Hong Kong. Foreign clients from Japan, America and across Europe could easily come to the British colony to meet with a production agent, who would help them recruit talent from mainland studios to complete projects. Shenzhen became a city of cartoon factories, churning out frames for TV series and movies around the globe.

.jpg)

Storyboards were created abroad with original drawings, but the grunt work was done in China – long, painful hours painting thousands of frames – cutting the production costs in half. Once the final ink and paint work was done, each frame would then be sent to Hong Kong for processing.

Chen recalls working on his first project in 1986 with a Japanese company. The project was the hit US series ThunderCats, animated in Japan – which in turn contracted out parts to China. A typical work day was 10 hours long. Artists were given a dormitory in which to sleep. The majority of employees came from provinces outside Guangdong.

Nevertheless, Shenzhen in the 1980s was a cultural oasis, according to Chen. “We loved watching TV in Shenzhen. Pearl Network showed so many foreign movies, we had never seen anything like that. We didn’t want to go home.”

For those growing up during the Cultural Revolution with a desire to draw, paint and create, Shenzhen in the 80s was the Holy Grail; a place where an artist could make a living following years when most found themselves solely producing propaganda.

We had to import everything. Pencils, paper, erasers, pencil sharpeners, all came from Western countries

Xu Ling also remembers the period very vividly. While today she works with Chen and Zhang as a producer and manager, she began her first job in the animation industry as an interpreter in 1988, working for a company called Pacific Rim. As she toiled her way up the ranks, she was occasionally required to attend meetings in the US. “In those days it was very unusual for someone from the mainland to travel on a business visa,” she remarks.

It was certainly a very different time. Shenzhen studios were not equipped with basic drawing materials, only labor. “We had to import everything. Pencils, paper, erasers, pencil sharpeners, all came from Western countries,” notes Xu.

Pacific Rim came under a lot of stress in 1988 when they helped make parts of The Little Mermaid, Disney’s last hand-painted celluloid animation. The film was sent to Pacific Rim frame by frame on large transparent plastic screens generated in California to be painted in Shenzhen.

“The drawings were controlled very strictly, and if one cell was painted wrong you could not keep it, you had to send it back. And you could not keep anything from the studio. That was the most strictly controlled project I ever worked on,” Xu recalls.

.jpg)

When the film was released, Disney neglected to put a single Chinese artists’ name in the credits. So overlooked by history is Pacific Rim that it is not even listed on IMDB. This despite the fact that the company had a hand in DuckTales, TaleSpin, An American Tail: Fievel Goes West – even Hammerman, the short-lived cartoon featuring the ‘U Can’t Touch This’ rapper.

The heyday of outsourcing has come and gone. With entire projects now done on computer, pencils and brushes serve as 20th-century relics. Pacific Rim closed in the late 1990s.

The 1997 handover of Hong Kong changed the playing field. Chinese artists could deal with clients directly rather than going through Hong Kong recruiters. A gradual appreciation of the yuan saw ink and paint work move to Vietnam, and the dawn of 3D animation brought India into the forefront as China’s biggest competitor. Local animators decided instead to focus on making their own cartoons for the local market.

One of the biggest challenges was (and still is) coming up with original material, as Becky Bristow witnessed first-hand. Bristow, a veteran of Pacific Rim who also worked in the development of dozens of iconic projects such as Garfield, The Cramp Twins and The Rugrats Movie, currently runs the animation program at Jinan Arts College in Guangzhou.

“Creativity can happen everywhere, it just has to be nurtured,” argues Bristow, yet her experience at Beijing University in the early 2000s taught her that building a practical college program is itself fraught with difficulty. When she tried to institute her method of allowing students to create their own animated shorts – a method she employed with success at the California Institute of the Arts – she hit a bureaucratic wall.

Pacific Rim had a hand in DuckTales, TaleSpin – even Hammerman, the short-lived cartoon featuring the ‘U Can’t Touch This’ rapper

The need for some kind of action was made crystal clear in June of 2008, when DreamWorks’ Kung Fu Panda hit Chinese screens. With enormous chagrin, the Ministry of Culture looked on as Middle Kingdom audiences packed cinemas to watch an American animation that was filled with Chinese elements. Why couldn’t we do this ourselves, the public asked? Well, one studio heard their cries, but the result was not a brilliant, original concept, but a bungled imitation of the DreamWorks success that only increased the humiliation of China’s animation industry: Legend of a Rabbit. Purportedly the first feature-length Chinese animation to be shown overseas, it bombed in the box office and was roundly ridiculed domestically and internationally.

Many critics said that the plot points were secondary issues compared to the animation itself, which looked amateur and cheap compared to Western creations. In response, more cash was invested into the sector. Bristow points out that throwing money at the industry doesn’t guarantee original ideas, however, and many new animation studios remain empty.

China’s animation hurdles are not just about playing catch up with the international community, but also getting projects green-lit by SAPPRFT censors. Like most mainland media, Chinese animators program for the authorities first and the audience second, since government approval (not audience approval) is what provides steady work. Typically, the cartoons that get waved through are child-friendly fluff like Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf (喜羊羊与灰太狼).

Corporate interest in animation has increased, with companies like Alibaba and Tencent starting to fund major projects, though Xu argues that mainland investors are often impatient with the creative process.

“They want an animation feature done in one year when the creative process takes at least two years,” she says.

When I ask Chen whether Chinese animators get the respect they deserve, he pauses and offers a matter of fact answer: “So much Chinese animation is just copying. What is there to admire in copying someone else’s project?”

China’s animation industry has been slow to find its feet, but at least it’s beginning to creakily move into gear. As Xu sums up the situation: “We worked on other people’s projects for a very, very long time. Now we are creating. Now we strictly produce our own work.”

.jpg)

//This story was conceived in collaboration with Lingnan Voices, a program by the Guangdong Radio and Television (GRT) Radio News Center English Service. To hear the full program, please visit http://e.rgd.com.cn/home/lingnanvoices/2015-07-27-2354.html or scan the QR code.

.jpg)

.jpg)

0 User Comments