French-Chinese author Aube Rey Lescure recently published her debut novel, River East, River West, a book that parallels her own experience growing up in 2000s Shanghai while caught in the cross-section of unfettered expat life and comparatively restrictive Chinese public school.

The tale embodies a stunning reversal of the East-to-West immigrant story through a bifurcation of both the main character Alva – whose personality is stuck between her American mother and unknown Chinese father – and the city in which she lives, Shanghai – a city split by the Huangpu River.

The book turns a critical eye towards the 'expat package' lifestyle of Shanghai in the early 2000s – a time when many foreigners "treated China like their playground," living in company-provided mansions with a slew of local servants – live-in maids, cooks, drivers, and daycare workers – to wait on their every whim.

The book weaves together story lines of China’s rapidly evolving capitalism – a "Coca-colonization" of the mainland – over the last few decades, while concurrently pulling back the curtain to reveal the pitfalls of this fast-paced expansion on an individual level.

We were lucky enough to sit down with Aube, who grew up in Shanghai, to learn more about what her life was like just a handful of years ago in the city, and how those stories came to life on the page.

Give us a brief synopsis of River East, River West, your debut novel with HarperCollins that was released this past January.

Fourteen-year-old Alva was born and raised in Shanghai and lives in Pudong’s Century Park neighborhood with her American expat mother, Sloan.

When Sloan unexpectedly marries their wealthy Chinese landlord, Lu Fang, Alva resents having to exchange a free-wheeling partnership for the claustrophobic lifestyle of middle-class Shanghai.

As Alva navigates the exam prep, paranoid competition, and absentee parenthood that reign over the hyper-regimented Chinese school system, she is drawn to the freedom of Shanghai’s expats, with their villas on well-guarded country clubs and the thrills of a city where foreigners can ostensibly act as they please.

Alternating sections of the novel reveal Lu Fang’s history with Sloan, dating back from their first encounter in the seaside city of Qingdao, when Lu Fang was a married clerk at a shipping yard and China had just let in its first wave of foreigners.

Aube Rey Lescure in Shanghai with her Chinese relatives (circa 1998)

What was the inspiration for writing this coming-of-age tale?

I grew up between northern China and Shanghai, and I spent much of my teenage years in Pudong, living in the Century Park neighborhood.

My mother was a French expat who’d been in China since the 80s, and my father is Chinese. I went to Chinese public schools for most of my childhood, and then two years of international school.

I wanted to capture the granularities of growing up in contemporary China and also portray these parallel versions of adolescence in a city like Shanghai that vary depending on your class and your nationality.

The Shanghai life in 2009-2010 and the teen expat nightlife was – in hindsight – truly intoxicating, but also unregulated and terrifying in many ways.

I wanted to explore both the regimentation of Chinese adolescence and the seemingly unbound expat youth.

Your background is in foreign policy. What was the impetus to dabble in journalism and ultimately publish your first book?

I studied international affairs with an eye towards US-China security issues in college, and I worked at a think tank in DC after graduation.

While in academia and research, I did want to explore the intricate relations between China and the West, but I found myself increasingly drawn to telling that story through essays and fiction.

While scrounging up a life as a freelance writer, I translated a lot of TV subtitles along with an academic book on Chinese economics. Unsurprisingly, writing a novel was a lot more thrilling and freeing.

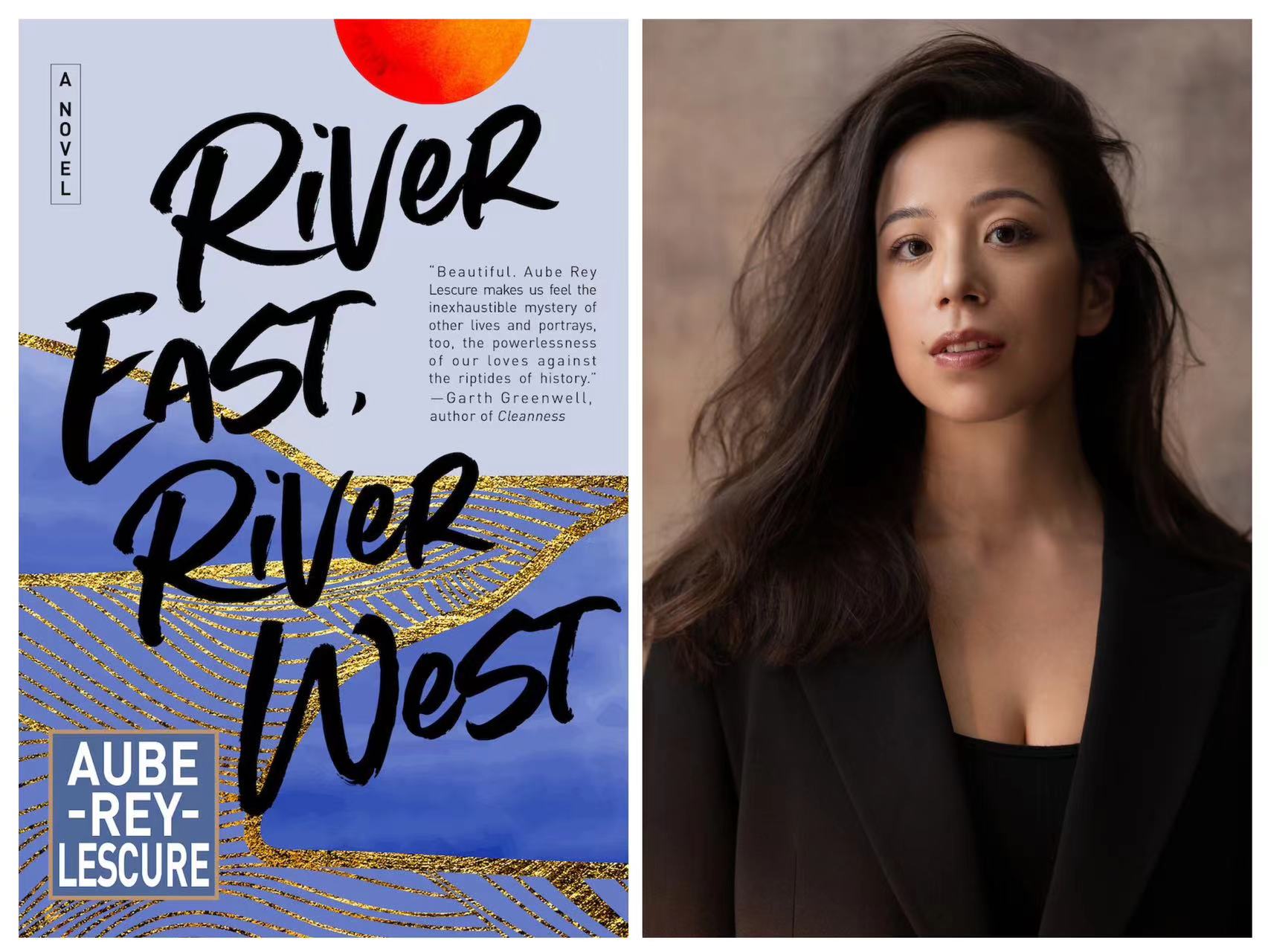

Aube Rey Lescure in Dalian public school (circa 2002)

How does River East, River West parallel your own upbringing?

A lot of the Alva sections parallel my childhood in terms of the locations and details. You can still find the streets and shops described in much of the novel’s Shanghai.

I was obsessed, like many of my Chinese classmates, with fishballs from FamilyMart; I did leak hentai on our class forum (like Alva did); and there was a 'DVD man' on my street – a mysterious concierge of cinema – who knew his customer’s individual tastes.

I also did partake in a lot of the risky expat teen nightlife once in international school, and some experiences still make me shudder when I look back on them as an adult (like how many adults in the industry were willingly enabling this scene).

Thankfully, in terms of the more dramatic and heartbreaking plot points of the book, those are fiction – me imagining the 'what-ifs' of what could have happened.

The book follows a duo of protagonists from two distinct generations and important eras in China’s recent history – jumping back and forth in time. What do you hope to convey to readers through this split-style leading character narration?

I wanted to challenge Alva’s myopia and narcissism as a teenage protagonist: she sees her new stepfather, Lu Fang, as an utterly average nouveau-riche businessman who benefited from China’s economic rise.

Alva has grown up in the post-90s era of China’s globalization; she lives with a Western mother and is used to seeing the foreign world in Shanghai. To her, it’s not so much new as inaccessible.

By introducing Lu Fang as a secondary narrator, and starting his timeline from the 1980s while simultaneously converging towards the present moment, we see how much depth and unknowability there is to his life story – the heartbreaks and parallels Alva does not even suspect.

I wanted to create dramatic irony for the reader by juxtaposing these two characters, the eras they inhabit, and highlight all their gaps in their knowledge of each other.

Like puzzle pieces that will never fit, only the reader will see the satisfying whole picture.

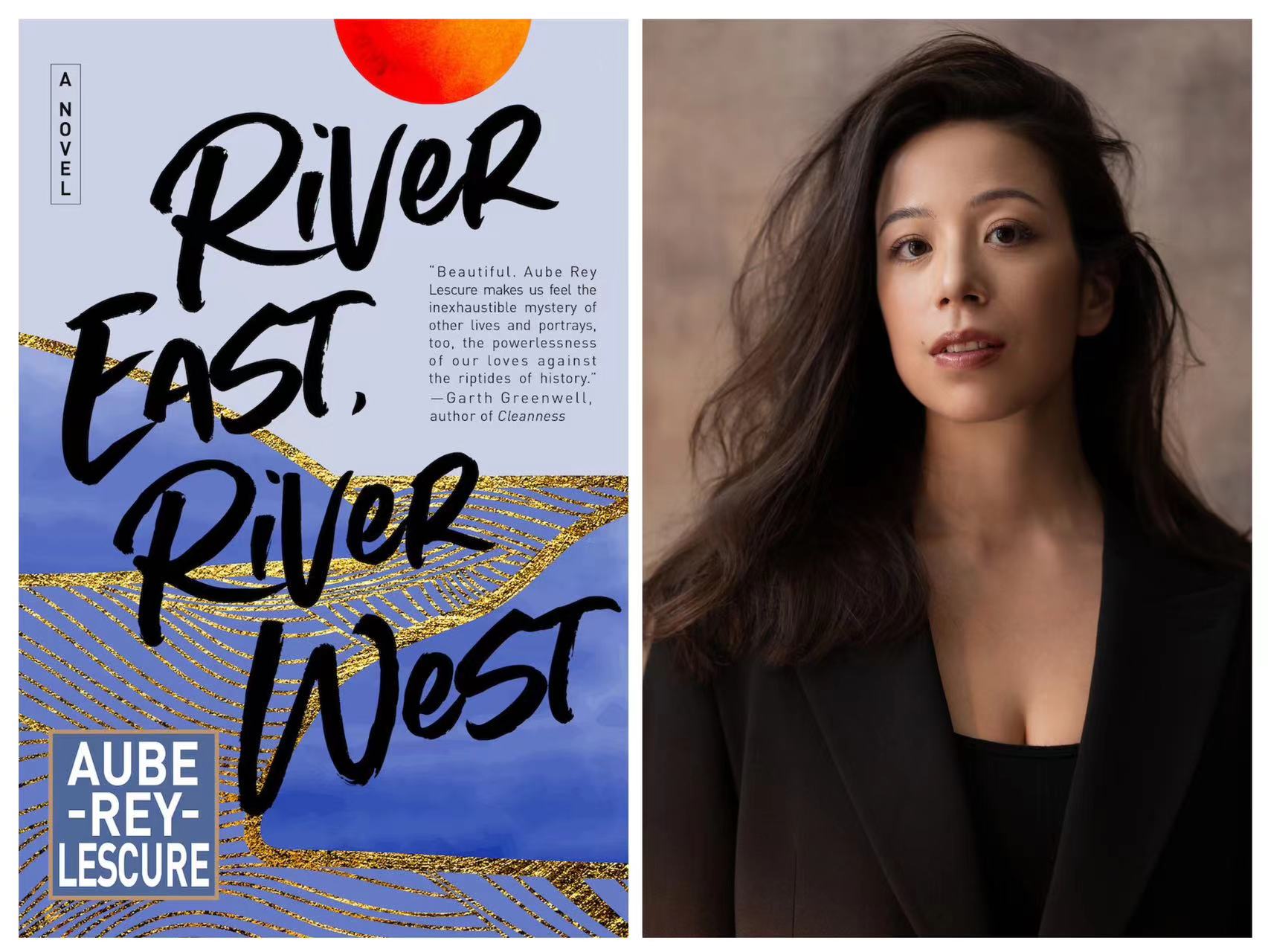

Aube Rey Lescure with her younger sister, Oceana, in Shanghai in 2014

Why the title River East, River West?

For the longest time, I didn’t have a title. I toyed with the words 'expatriation' and 'alienation,' for a while. The working title was The Foreigner. But these didn’t feel quite right.

River East and River West, of course, refers to Pudong and Puxi, and are an homage to Shanghai. I also wanted to draw out the elements of migration, of East and West, but play with the concept of rivers.

Huangpu River looms large in the story, but there’s also the Yalu River in Lu Fang’s timeline – a river that divides China and North Korea – where China is West compared to North Korea.

In this sense, the cultural illusions we have of what’s beyond are not just about Asia and the West, but simply the lives we imagine beyond certain borders and divisions.

The deep divides in a rapidly developing China, the concept of cross-cultural identity, and the building of bridges between locals and expats in China throughout the last few decades are key themes throughout the novel.

What are the main takeaways you would like readers to receive from this book?

I want to bring a more critical eye to contemporary expat culture in China that is still too seldom discussed in literature. Growing up, the level of indifference and privilege I witnessed in expat communities in Shanghai shocked me.

In the context of a multi-ethnic, cross-cultural family, I wanted to emphasize the point of view of Chinese characters and portray how cultural dynamics between expats and local residents of China could have huge ramifications on both sides.

For example, how does a young Chinese person view their interactions with less than well-behaved expat contemporaries?

How do children growing up in expat enclaves view their own status and position vis-a-vis their Chinese peers? (i.e. are they educated to respect, be interested in, and be invested in their host society, or be oblivious at best and condescending at worst?)

Some readers who were expats in China have told me that this book made them question some internalized assumptions and attitudes they held, which gladdened me.

That said, there’s a lot of satire and skewing of expat characters in this book; I also wanted to portray that they are not a monolithic community.

Especially today, there’s ever-more welcome room for nuance and sensitivity to the way we can discuss expat presence in China given the complexities of the country in 2024.

We are excited to see That’s Shanghai make an appearance a handful of times in your novel, as it revolves around expat dynamics and culture in the city. What role did English media play in your life growing up in Shanghai back in the 2000s?

I would pick up That’s Shanghai magazines whenever I saw a stack outside restaurants, in malls, in waiting rooms. To me, it was a window into a version of expat Shanghai life that seemed mysterious and glamorous.

I remember bringing the magazine to my Chinese middle school to read in-between classes and going through its articles and listings as a kind of escapism. All of these concerts, bars, restaurants, exhibits seemed so international, yet were taking place right here in my city!

But they also felt removed, like the life lived by another set of people so different from me and my Chinese classmates.

Later, when I went to international school, I felt like I was squarely in the world of That’s Shanghai. And it’s undoubtedly a thrilling, intoxicating world – intoxication that does come with its dark sides, but also provides these incredible highs of living in a seemingly limitless metropolis.

How can That’s Shanghai readers get ahold of a copy of River East, River West?

Right now, the easiest way is probably to get an ebook or Kindle version through any major online retailer – Barnes and Noble, Amazon, etc. I wish independent bookstores shipped to China!

Otherwise, the audiobook is also excellent, and is available on Audible and Spotify.

[All images courtesy of Aube Rey Lescure]

0 User Comments